Rethinking Stress Part I: A Brief Introduction to Eustress

Why do many people enjoy the thrill of riding a rollercoaster, skydiving, or going to a scary movie? Such situations lead to a physiological stress response; the heart rate increases, stress hormones release (e.g. adrenaline and cortisol), blood is redirected so important organs such as the brain and heart receive more blood flow, and more. Yet we wouldn’t describe such situations as stressful; the word ‘thrilling’ or ‘exciting’ might be used instead. They are enjoyable, positive experiences of stress.

Not everyone finds such activities thrilling, however. For some, it might be the feeling of butterflies in the stomach before or during a playoff hockey game–whether you’re a player in the game or a parent watching. Or it might be the stress from the kitchen chaos of juggling multiple ingredients, burners, and bringing everything together when cooking an exquisite meal. The stress from working out, the high from running, the mental clarity before a big exam. All of these are examples of stress, but they are a good kind of stress; the kind of stress that prepares us psychologically and physiologically for peak performance, without making us feel overwhelmed. It’s the ‘sweet spot’ of stress.

Scientists and physicians have a word for this type of stress: eustress, or “good stress,” where eu- comes from the Greek prefix for “good.” What differentiates eustress from stress, or the negative distress, is simply how one perceives the stressor. Were you the student who buckled under the pressure of a big exam, feeling overwhelmed and perceiving the exam as a negative threat; or were you the student who felt excited about the exam, ready to take on the challenge and prove yourself? The former would have experienced stress or distress, while the latter would be experiencing eustress.

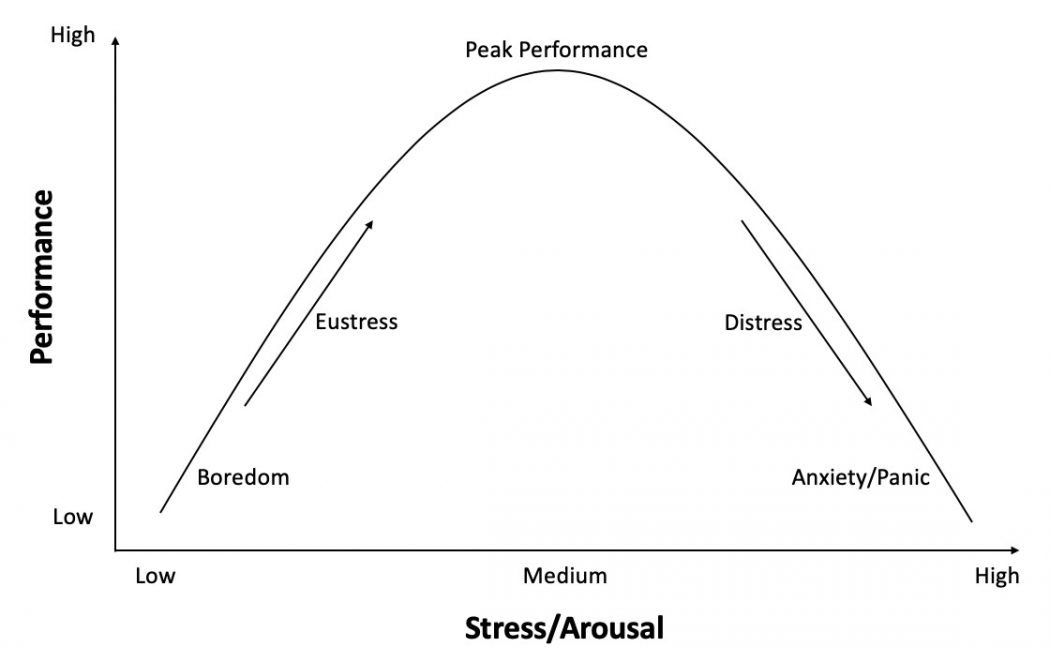

This topic is related to the Yerkes-Dodson law, which asserts that arousal, or stress, and performance are directly related. As stress or arousal increases, so too does performance, up to an optimal point, before performance begins falling. A diagram illustrating this relationship is shown below.

So, stress can be good, can help us reach peak performance, and contributes to our growth. Many people struggle with the mindset to deal with stress in this positive manner, however, and stress becomes a detrimental part of their lives. In Part II of “Rethinking Stress,” we will examine recent academic literature about how reappraising stress can cause you to positively respond to stressors, and identify ways you can adapt your mindset to optimize your response to stress.